Advent of Code 2023: Days 1 and Day 2

An example of what we’ll be doing in this article

Yes, it’s this time of the year again! While we’re all enjoying a few weeks of festive activities and a bit of well-deserved quality time with our loved ones, some of us are deliberately choosing to spend this time solving some random programming challenges.

Now if you ask me, what I really like about Advent of Code, is the creative and fun ways that some programmers approach each new puzzle. See, for people like me who couldn’t care less about competition and leaderboards, each new season of Advent of Code is an opportunity to discover new and challenging ways to stimulate my limited problem-solving skills. Simply head over to YouTube, search for advent of code + [year] + [whatever language you can think of] and you’ll quickly find yourself watching videos of people trying to solve coding puzzles in absolutely every single programming language that you can think of. As someone who’s much more interested in the creative and fun aspects of the whole exercise, seeing people breeze through each new exercise using COBOL, Zig, or Haskell is an absolutely mesmerising experience.

Now if you’ve been following me for a little while, you’re then probably aware that I started learning TypeScript about a year or so ago. The reasons why I decided to embark on this journey are quite simple: I love JavaScript, and I’m comfortable with static typing. I remember that it simply felt like a logical thing to do back when I started in late 2021. Over a year later, I have to say that though I unfortunately don’t get to utilise TypeScript as often as I’d want to, getting to learn this language is a decision I haven’t regretted even for a second. It is fun, the types system is much complex than I ever imagined it would be, and I’ve discovered some really interesting ways to play around with types definitions. For instance, I recently stumbled upon this StackOverflow post that shows how to define a decorator that enforces an interface on static members. We’re literally talking about a function that works exclusively on types, and I have to admit that after reading through that post I still don’t even know why and how it works.

Anyway, as we’re approaching the end of the year, I too thought that it’d be pretty fun to put my new and still feeble skills to the test, by taking on the yearly Advent of Code challenge entirely in TypeSript.

Without further ado, let’s get started!

Day 1: Elves write some weird stuff

One quick note before we start: each exercise on the Advent of Code website comes in the form of a simple .txt file. However, as I’m using an online TypeScript playground named Playcode.io, there isn’t an easy way for me to upload a .txt file onto that coding environment. We’ll therefore be using the examples provided with each exercise to test and validate our code. That shouldn’t really affect the logic of what we’re trying to achieve today though.

With this out of the way, here’s our first problem:

The […] document consists of lines of text; each line originally contained a specific […] value that the Elves now need to recover. On each line, the calibration value can be found by combining the first digit and the last digit (in that order) to form a single two-digit number. For example:

1abc2

pqr3stu8vwx

a1b2c3d4e5f

treb7uchet

In this example, the calibration values of these four lines are 12, 38, 15, and 77. Adding these together produces 142. Consider your entire calibration document. What is the sum of all of the calibration values?

Well this sounds pretty straightforward to me. What we need to do here, is extract the first and last integer contained within each line, or extract the same integer twice if there’s only one. Then we’ll simply store these values somewhere, and sum them.

Now here’s how I think we should approach this exercise:

- We create an Object where each unique key maps to a row number. The value associated with each of these keys is an array that contains all the integers found within each individual row

- We loop through each row, then through each unique character within that row

- If this character happens to be an integer, we push it to the aforementioned array

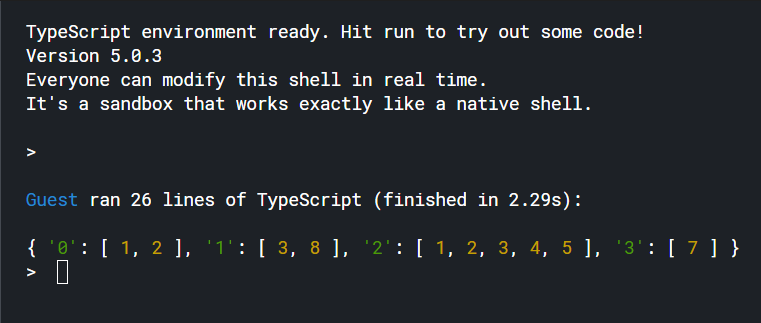

If we consider the example provided earlier, we’d eventually end up with something like this:

{

0: [1,2],

1: [3,8],

2: [1,2,3,4,5],

3: [7]

}

- We then loop (again!) through that Object, take the integers located at index

[0]and[-1]from each array, and store them in a separate array - We sum the integers within that array

Easier said than done? Let’s see! If you remember, here’s what the data we’ll be using to validate our code looks like:

const text: string[] = [

"1abc2",

"pqr3stu8vwx",

"a1b2c3d4e5f",

"treb7uchet"

];

Remember earlier, when we said we’d need an object to store the row numbers as keys, and the integers we find as values? We can define it as follows:

type Result = {

[key: number]: number[];

};

Our next step is to create three separate functions.

A first one that loops through each individual character, uses regular expressions to assert whether that character could be parsed into an integer or not, and stores these character if they pass our simple test:

const getAllIntegers = (data: string[]): Result => {

let result: Result = {};

for (let i = 0; i < data.length; i++) {

result[i] = [];

for (let char of data[i]) {

let temp_char: any = new RegExp(/^[0-9]/);

if (temp_char.test(char)) {

result[i].push(parseInt(char));

}

}

}

return result;

}

console.log(getAllIntegers(text));

Then a second function, that takes the first and last integers within each row (and the same value twice if there’s only one integer stored in an array). We could arguably have embedded this step within the previous function, but for the sake of clarity I just just thought that we might as well keep everything separated:

const getSelectedIntegers = (data: Result): number[] => {

let result: number[] = [];

for (let d in data) {

let first_integer: number = data[d][0];

let last_integer: number = data[d].slice(-1)[0];

result.push(first_integer);

result.push(last_integer);

}

return result;

};

const first: Result = getAllIntegers(text);

const second: number[] = getSelectedIntegers(first)

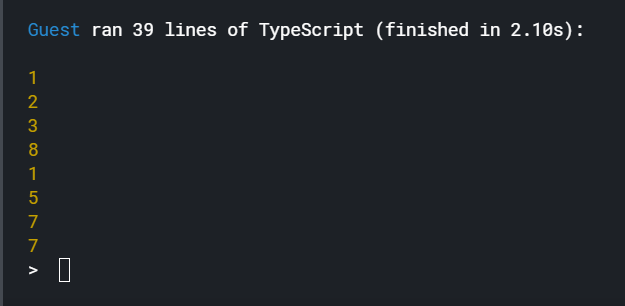

second.forEach(i => console.log(i))

We get this nice array and all the integers that we had to extract, that we can just sum through our third and last function:

const getFinalResults = (data: number[]): number => {

let result: number = 0;

data.forEach(nums => {result += nums});

console.log(`The answer for puzzle 1 is:\n\n\t${result}\n`);

return result;

};

const first: Result = getAllIntegers(text);

const second: number[] = getSelectedIntegers(first)

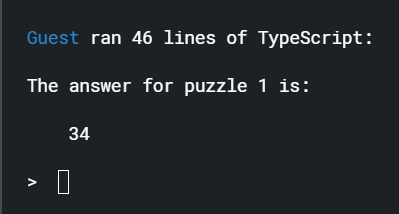

getFinalResults(second);

Seems like we successfully completed the first exercise!

Day 2: Elves seem to also be into gambling

As can be expected, the puzzle for Day 2 is slightly more difficult than the one we just went through. Actually, allow me to rephrase this: it’s not that the logic involved is particularly complex, but going through this new exercise will definitely involve a few more steps.

Anyway, here’s what the challenge looks like this time:

[…] the Elf shows you a small bag and some cubes which are either red, green, or blue. Each time you play this game, he will hide a secret number of cubes of each color in the bag. […] You play several games and record the information from each game. […] The record of a few games might look like this:

Game 1: 3 blue, 4 red; 1 red, 2 green, 6 blue; 2 green

Game 2: 1 blue, 2 green; 3 green, 4 blue, 1 red; 1 green, 1 blue

Game 3: 8 green, 6 blue, 20 red; 5 blue, 4 red, 13 green; 5 green, 1 red

Game 4: 1 green, 3 red, 6 blue; 3 green, 6 red; 3 green, 15 blue, 14 red

Game 5: 6 red, 1 blue, 3 green; 2 blue, 1 red, 2 green

In the example above, games 1, 2, and 5 would have been possible. […] However, game 3 would have been impossible […], game 4 would also have been impossible. […] If you add up the IDs of the games that would have been possible, you get 8.

Determine which games would have been possible if the bag had been loaded with only 12 red cubes, 13 green cubes, and 14 blue cubes. What is the sum of the IDs of those games?

From the get go, and as mentioned earlier, this is probably going to require some more advanced string parsing techniques:

- We create an object where the integers contained after the term “Game” in each row are the keys

- We create a series of nested objects within our first object, where the terms “red”, “green”, and “blue” are the keys and their corresponding values an array of integers

- We split each row by white space, loop through this array, look for the terms “red”, “green”, and “blue” and push the elements at position

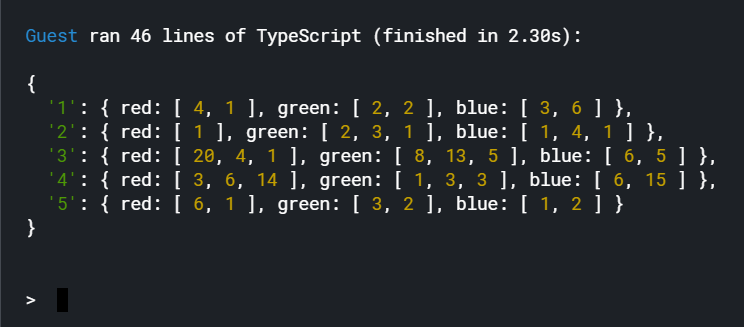

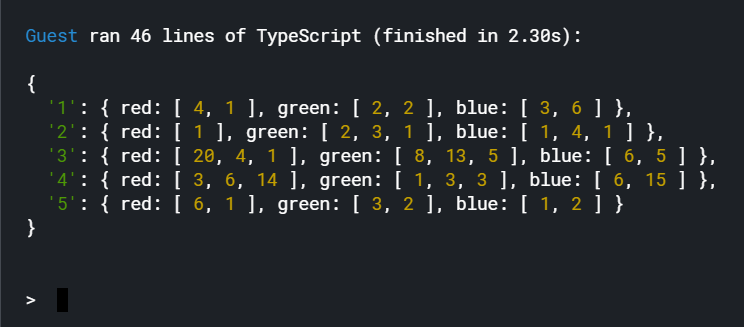

[-1]to the array of integers in our aforementioned nested object. So that our main object now looks like this:

{

1: {

red: [4,1],

green: [2,2],

blue: [3,6],

},

2: {

red: [1],

green: [2,3,1],

blue: [1,4,1],

},

etc..

- We set up thresholds for each colour (in this case 12, 13, and 14)

- A simple loop through each array checks if the values are above their corresponding thresholds and returns a boolean

- We now know which game has some values above the thresholds, and we can exclude them

- All that’s left to do is sum the keys of the remaining games

Our approach might seem a little bit convoluted, but I’m sure it will do the job!

Let’s get started:

const puzzle: string[] = [

"Game 1: 3 blue, 4 red; 1 red, 2 green, 6 blue; 2 green",

"Game 2: 1 blue, 2 green; 3 green, 4 blue, 1 red; 1 green, 1 blue",

"Game 3: 8 green, 6 blue, 20 red; 5 blue, 4 red, 13 green; 5 green, 1 red",

"Game 4: 1 green, 3 red, 6 blue; 3 green, 6 red; 3 green, 15 blue, 14 red",

"Game 5: 6 red, 1 blue, 3 green; 2 blue, 1 red, 2 green"

];

We first need to define the types for our two main objects:

type All_Games = {

[key: string]: {[key: string]: number[]}

;}

type Possible_Games = {

[key: number]: boolean[]

};

Which leads us onto our first function. As discussed earlier, the game variable will serve to store each game ID as keys within our result object. Once we’ve splitted each row, we look for the terms “red”, “green”, and “blue” and parse each element at position [-1] as an integer before pushing them into an array of type number[].

const getAllGames = (data: string[]): All_Games => {

let result: All_Games = {};

for (let d of data) {

let game: string = d.split(":")[0].split(" ")[1];

let cubes: string = d.split(":")[1];

let cube: string[] = cubes.split(" ");

result[game] = {};

result[game]["red"] = [];

result[game]["green"] = [];

result[game]["blue"] = [];

for (let i = 0; i < cube.length; i++) {

if (cube[i].includes("red")) {

result[game]["red"].push(parseInt(cube[i-1]));

}

else if (cube[i].includes("green")) {

result[game]["green"].push(parseInt(cube[i-1]));

}

else if (cube[i].includes("blue")) {

result[game]["blue"].push(parseInt(cube[i-1]));

}

}

}

return result;

};

const all_games: All_Games = getAllGames(puzzle);

console.log(all_games);

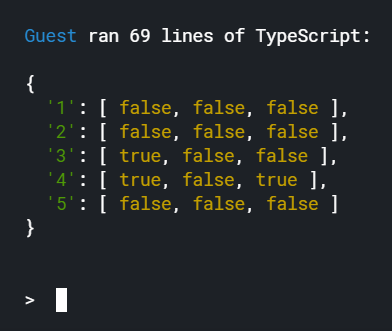

Alright, that worked, but we’re far from done! Our next function loops through our arrays of integers and checks whether each element is lower than the corresponding values stored in the thresholds variable or not. The .some() method returns a boolean value, which is pushed into an array defined by the type Possible_Games.

const getPossibleGames = (data: All_Games): Possible_Games => {

let possible_games: Possible_Games = {};

const thresholds: number[] = [12,13,14];

for (let game in data) {

possible_games[parseInt(game)] = [];

for (let g in data[game]) {

let cubes: number[] = data[game][g];

if (g == "red") {

possible_games[parseInt(game)].push(cubes.some(c => c > thresholds[0]));

}

else if (g == "green") {

possible_games[parseInt(game)].push(cubes.some(c => c > thresholds[1]));

}

else if (g == "blue") {

possible_games[parseInt(game)].push(cubes.some(c => c > thresholds[2]));

}

}

}

return possible_games;

};

const all_games: All_Games = getAllGames(puzzle);

const all_possible_games: Possible_Games = getPossibleGames(all_games);

console.log(all_possible_games);

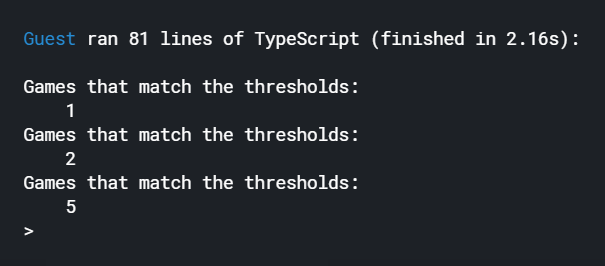

Almost there. All that’s left to do at this point is detect the presence of the boolean value true within each array. Each key whose corresponding values matches our detector gets pushed into a new array named result:

const getWinningGames = (data: Possible_Games): number[] => {

let result: number[] = [];

for (let game in data) {

//console.log(data[game]);

if (!data[game].includes(true)) {

result.push(parseInt(game));

}

}

return result;

};

const all_games: All_Games = getAllGames(puzzle);

const all_possible_games: Possible_Games = getPossibleGames(all_games);

const winning_games: number[] = getWinningGames(all_possible_games);

winning_games.forEach(w => console.log(`Games that match the thresholds:\n\t${w}`))

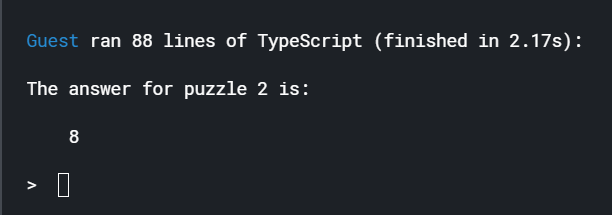

Onto our fourth and final function, which is the exact same piece of code that we wrote earlier for the Day 1 puzzle. As programmers are lazy by nature, we’re absolutely fine with this reutilising getFinalResults() one last time:

const getFinalResults = (data: number[]): number => {

let result: number = 0;

data.forEach(nums => {result += nums});

console.log(`The answer for puzzle 2 is:\n\n\t${result}\n`);

return result;

};

const all_games: All_Games = getAllGames(puzzle);

const all_possible_games: Possible_Games = getPossibleGames(all_games);

const winning_games: number[] = getWinningGames(all_possible_games);

getFinalResults(winning_games);

And it looks like we’ve done it! Now dear reader, I hope you enjoyed this article, and feel free to reach out to me if you’ve taken a different approach, or used some funky language!